Drehung: Unterschied zwischen den Versionen

User (Diskussion | Beiträge) Keine Bearbeitungszusammenfassung |

Admin (Diskussion | Beiträge) K (→Euler-Winkel) |

||

| (8 dazwischenliegende Versionen von 2 Benutzern werden nicht angezeigt) | |||

| Zeile 23: | Zeile 23: | ||

beschreibt eine Drehung des "Vektors" z um den Winkel ''φ''. |

beschreibt eine Drehung des "Vektors" z um den Winkel ''φ''. |

||

== |

==Drehung im Raum== |

||

Die Drehung im Raum lässt sich mit den Matrizen ''R<sub>ij</sub>'' der Drehgruppe ''SO<sub>3</sub>'' beschreiben |

|||

<math>\begin{pmatrix} x' \\ y' \\ z' \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} r_{xx} \ r_{xy} \ r_{xz} \\ r_{yx} \ r_{yy} \ r_{yz} \\ r_{zx} \ r_{zy} \ r_{zz}\end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} x \\ y \\ z \end{pmatrix} </math> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

Die Matrizen der Drehgruppe ''SO<sub>3</sub>'' haben folgende Eigenschaften |

|||

*Die [[Determinante]] ist gleich eins |

|||

*Zeilen und Spalten stehen orthogonal aufeinander, das Skalarprodukt von zwei verschiedenen Zeilen oder Spalten ist gleich Null |

|||

*die Tansponierte Matrize (''R<sub>ji</sub>'') ist die inverse |

|||

===Drehung um eine gegebene Achse=== |

|||

Drehung um die ''x''-Achse des Koordinatensystems |

|||

<math> |

|||

\begin{pmatrix} |

|||

1 & 0 & 0 \\ |

|||

0 & \cos \varphi & -\sin \varphi \\ |

|||

0 & \sin \varphi & \cos \varphi |

|||

\end{pmatrix} |

|||

</math> |

|||

Drehung um die ''y''-Achse des Koordinatensystems |

|||

<math> |

|||

\begin{pmatrix} |

|||

\cos \varphi & 0 & \sin \varphi \\ |

|||

0 & 1 & 0 \\ |

|||

-\sin \varphi & 0 & \cos \varphi |

|||

\end{pmatrix} |

|||

</math>, |

|||

Drehung um die ''z''-Achse des Koordinatensystems |

|||

<math> |

|||

\begin{pmatrix} |

|||

\cos \varphi & -\sin \varphi & 0 \\ |

|||

\sin \varphi & \cos \varphi & 0 \\ |

|||

0 & 0 & 1 |

|||

\end{pmatrix} |

|||

</math> |

|||

Drehung um eine Achse, die parallel zum [[Einheitsvektor]] '''''v''''' =(''v<sub>x</sub>,v<sub>y</sub>,v<sub>z</sub>'')<sup>T</sup> ausgerichtet ist |

|||

<math> |

|||

\begin{pmatrix} |

|||

\cos \varphi +v_x^2 \left(1-\cos \varphi\right) & v_x v_y \left(1-\cos \varphi\right) - v_z \sin \varphi & v_x v_z \left(1-\cos \varphi\right) + v_y \sin \varphi \\ |

|||

v_y v_x \left(1-\cos \varphi\right) + v_z \sin \varphi & \cos \varphi + v_y^2\left(1-\cos \varphi\right) & v_y v_z \left(1-\cos \varphi\right) - v_x \sin \varphi \\ |

|||

v_z v_x \left(1-\cos \varphi\right) - v_y \sin \varphi & v_z v_y \left(1-\cos \varphi\right) + v_x \sin \varphi & \cos \varphi + v_z^2\left(1-\cos \varphi\right) |

|||

\end{pmatrix} |

|||

</math>. |

|||

Diese Transformationsmatix kann in eine etwas übersichtlichere Darstellung gebracht werden |

|||

<math> |

|||

\begin{pmatrix} v_x^2 \ & v_x v_y \ & v_x v_z \\ v_y v_x \ & v_y^2 \ & v_y v_z \\ v_z v_x \ & v_z v_y \ & v_z^2 \end{pmatrix} + |

|||

\begin{pmatrix} 1 - v_x^2 \ & -v_x v_y \ & -v_x v_z \\ -v_y v_x \ & 1 - v_y^2 \ & -v_y v_z \\ -v_z v_x \ & -v_z v_y \ & 1 - v_z^2 \end{pmatrix}\cos \varphi + |

|||

\begin{pmatrix} 0 \ & -v_z \ & v_y \\ v_z \ & 0 \ & -v_x \\ -v_y \ & v_x \ & 0 \end{pmatrix} \sin \varphi |

|||

</math> |

|||

===Euler-Winkel=== |

|||

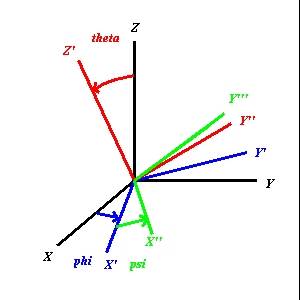

[[Bild:Eulerwinkel.jpg|thumb|die drei Eulerwinkel]] |

|||

Die Drehungen im Raum bilden eine kontinuierliche Gruppe (''SO<sub>3</sub>'') mit drei freien Parametern. Folglich kann jede beliebige Drehung durch drei hintereinander geschaltete "Elementardrehungen" erzeugt werden. Häufig dreht man zuerst um einen Winkel ''φ'' um die ''z''-Achse des Koordinatensystems, dann um den Winkel ''θ'' um die gedrehte ''x''-Achse und zuletzt um den Winkel ''ψ'' um die neu ausgerichtete ''z''-Achse |

|||

<math> |

|||

\begin{pmatrix} |

|||

\cos \psi \cos \varphi - \cos \theta \sin \varphi \sin \psi |

|||

& - \sin \psi \cos \varphi - \cos \theta \sin \varphi \cos \psi |

|||

& \sin \theta \sin \varphi \\ |

|||

\cos \psi \sin \varphi + \cos \theta \cos \varphi \sin \psi |

|||

& - \sin \psi \sin \varphi + \cos \theta \cos \varphi \cos \psi |

|||

& - \sin \theta \cos \varphi \\ |

|||

\sin \psi \sin \theta |

|||

& \cos \psi \sin \theta |

|||

& \cos \theta |

|||

\end{pmatrix} |

|||

</math> |

|||

Ist eine beliebige Drehung in Form der Transformationsmatrix ''R<sub>ij</sub>'' gegeben, können die Eulerwinkel in drei Schritten berechnet werden |

|||

#Berechnung des Winkels ''θ'': <math>\theta = \arccos (r_{zz})</math> |

|||

#Berechnung des Winkels ''ψ'': <math>\psi = \arctan \begin{pmatrix} \frac {r_{zx}}{r_{zy}} \end{pmatrix}</math> |

|||

#Berechnung des Winkels ''φ'': <math>\varphi = \arctan \begin{pmatrix} - \frac {r_{xz}}{r_{yz}} \end{pmatrix}</math> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Kategorie:Rot]] |

[[Kategorie:Rot]] |

||

Aktuelle Version vom 7. Januar 2007, 18:27 Uhr

Ein starrer Körper kann um eine beliebige Achse gedreht werden. Dabei drehen sich alle Verbindungslinien auf dem Körper um den gleichen Drehwinkel. Wird der Körper mehrmals um die gleiche Achse gedreht, lassen sich alle Eigenschaften der Drehbewegung in einer Ebene, die normal zur Achse steht, untersuchen. Die totale Drehung hängt dann nicht von der Reihenfolge der einzelnen Operationen ab.

Die allgemeine Drehung eines Körpers wird durch die Richtung der Achse und den Drehwinkel beschrieben. Dreht man einen Körper mehrmals um verschiedene Achsen, hat die Reihenfolge der einzelnen Operationen einen wesentlichen Einfluss auf die Gesamtdrehung.

Mathematisch gesehen bilden die Drehopertionen eine Gruppe. Die Menge der Drehungen um eine festgehaltene Achse kann mit Hilfe der SO2, alle Drehungen im Raum mit Hilfe der SO3 beschrieben werden.

Drehung in der Ebene

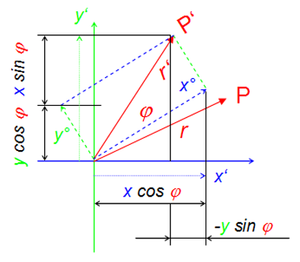

Bei einer ebenen Drehung gehe ein Punkt P in den Punkt P' und der zugehörige Orstvektor r in den Vektor r' über. Zerlegt man den Ortsvektor r bezüglich eines Koordinatensystems in die Komponenten x und y (mitgedreht: x° und y°), können die Komponenten des gedrehten Vektors (x' und y' ) aus den Komponenten des ursprünglichne Vektors berechnet werden

[math]x' = x \cos \varphi - y \sin \varphi [/math]

[math]y' = x \sin \varphi + y \cos \varphi [/math]

Diese Drehung lässt sich mit Hilfe der Matrizenrechnung kompakter formulieren

[math]\begin{pmatrix} x' \\ y' \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} \cos \varphi \ -\sin \varphi \\ \sin \varphi \ \cos \varphi \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} x \\ y \end{pmatrix}[/math]

Ordnet man den zu drehenden Punkten je eine komplexe Zahl z zu, wobei die x-Komponente des Ortsvektors r dem Realteil und die y-Komponente dem Imaginärteil der komplexen Zahl entspricht, kann die Drehung in der komplexen Ebene mittels einer Multiplikation mit der Zahl ei φ beschrieben werden. Die Operation

[math]z' = e^{i \varphi} z[/math]

beschreibt eine Drehung des "Vektors" z um den Winkel φ.

Drehung im Raum

Die Drehung im Raum lässt sich mit den Matrizen Rij der Drehgruppe SO3 beschreiben

[math]\begin{pmatrix} x' \\ y' \\ z' \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} r_{xx} \ r_{xy} \ r_{xz} \\ r_{yx} \ r_{yy} \ r_{yz} \\ r_{zx} \ r_{zy} \ r_{zz}\end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} x \\ y \\ z \end{pmatrix} [/math]

Die Matrizen der Drehgruppe SO3 haben folgende Eigenschaften

- Die Determinante ist gleich eins

- Zeilen und Spalten stehen orthogonal aufeinander, das Skalarprodukt von zwei verschiedenen Zeilen oder Spalten ist gleich Null

- die Tansponierte Matrize (Rji) ist die inverse

Drehung um eine gegebene Achse

Drehung um die x-Achse des Koordinatensystems

[math] \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & \cos \varphi & -\sin \varphi \\ 0 & \sin \varphi & \cos \varphi \end{pmatrix} [/math]

Drehung um die y-Achse des Koordinatensystems

[math] \begin{pmatrix} \cos \varphi & 0 & \sin \varphi \\ 0 & 1 & 0 \\ -\sin \varphi & 0 & \cos \varphi \end{pmatrix} [/math],

Drehung um die z-Achse des Koordinatensystems

[math] \begin{pmatrix} \cos \varphi & -\sin \varphi & 0 \\ \sin \varphi & \cos \varphi & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix} [/math]

Drehung um eine Achse, die parallel zum Einheitsvektor v =(vx,vy,vz)T ausgerichtet ist

[math] \begin{pmatrix} \cos \varphi +v_x^2 \left(1-\cos \varphi\right) & v_x v_y \left(1-\cos \varphi\right) - v_z \sin \varphi & v_x v_z \left(1-\cos \varphi\right) + v_y \sin \varphi \\ v_y v_x \left(1-\cos \varphi\right) + v_z \sin \varphi & \cos \varphi + v_y^2\left(1-\cos \varphi\right) & v_y v_z \left(1-\cos \varphi\right) - v_x \sin \varphi \\ v_z v_x \left(1-\cos \varphi\right) - v_y \sin \varphi & v_z v_y \left(1-\cos \varphi\right) + v_x \sin \varphi & \cos \varphi + v_z^2\left(1-\cos \varphi\right) \end{pmatrix} [/math].

Diese Transformationsmatix kann in eine etwas übersichtlichere Darstellung gebracht werden

[math] \begin{pmatrix} v_x^2 \ & v_x v_y \ & v_x v_z \\ v_y v_x \ & v_y^2 \ & v_y v_z \\ v_z v_x \ & v_z v_y \ & v_z^2 \end{pmatrix} + \begin{pmatrix} 1 - v_x^2 \ & -v_x v_y \ & -v_x v_z \\ -v_y v_x \ & 1 - v_y^2 \ & -v_y v_z \\ -v_z v_x \ & -v_z v_y \ & 1 - v_z^2 \end{pmatrix}\cos \varphi + \begin{pmatrix} 0 \ & -v_z \ & v_y \\ v_z \ & 0 \ & -v_x \\ -v_y \ & v_x \ & 0 \end{pmatrix} \sin \varphi [/math]

Euler-Winkel

Die Drehungen im Raum bilden eine kontinuierliche Gruppe (SO3) mit drei freien Parametern. Folglich kann jede beliebige Drehung durch drei hintereinander geschaltete "Elementardrehungen" erzeugt werden. Häufig dreht man zuerst um einen Winkel φ um die z-Achse des Koordinatensystems, dann um den Winkel θ um die gedrehte x-Achse und zuletzt um den Winkel ψ um die neu ausgerichtete z-Achse

[math] \begin{pmatrix} \cos \psi \cos \varphi - \cos \theta \sin \varphi \sin \psi & - \sin \psi \cos \varphi - \cos \theta \sin \varphi \cos \psi & \sin \theta \sin \varphi \\ \cos \psi \sin \varphi + \cos \theta \cos \varphi \sin \psi & - \sin \psi \sin \varphi + \cos \theta \cos \varphi \cos \psi & - \sin \theta \cos \varphi \\ \sin \psi \sin \theta & \cos \psi \sin \theta & \cos \theta \end{pmatrix} [/math]

Ist eine beliebige Drehung in Form der Transformationsmatrix Rij gegeben, können die Eulerwinkel in drei Schritten berechnet werden

- Berechnung des Winkels θ: [math]\theta = \arccos (r_{zz})[/math]

- Berechnung des Winkels ψ: [math]\psi = \arctan \begin{pmatrix} \frac {r_{zx}}{r_{zy}} \end{pmatrix}[/math]

- Berechnung des Winkels φ: [math]\varphi = \arctan \begin{pmatrix} - \frac {r_{xz}}{r_{yz}} \end{pmatrix}[/math]